- Home

- Kate Fulford

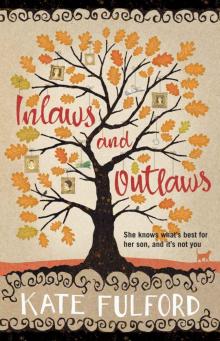

In-Laws and Outlaws

In-Laws and Outlaws Read online

IN-LAWS AND OUTLAWS

KATE FULFORD

All Rights Reserved

Copyright © Kate Fulford 2017

This first edition published in 2017 by:

Thistle Publishing

36 Great Smith Street

London

SW1P 3BU

www.thistlepublishing.co.uk

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 33

CHAPTER 1

“I’m a writer.” I said in reply to Marjorie’s enquiry. I’m not, but I have done the occasional bit of copywriting. I once did a poster for a friend of mine who has a fruit and veg stall on Chiswick High Road. It said ‘Mangoes Bananas’ next to a picture of a man who clearly had mental health issues. Alf thought it was very funny and put it on the side of his van. Unfortunately the Advertising Standards Authority found it rather less amusing but for a while I was one of the most widely read writers in that neck of the woods.

“Anything I might have read?” Marjorie asked, although not with any particular enthusiasm. I had the distinct impression that, despite her follow up question, Marjorie wasn’t in the least bit interested in my answer. She had asked me all sorts of questions in the short time I had spent with her but she did so, I felt, more in an attempt to unsettle me and not because she had any desire to get to know me better. I should explain that I was a few months into a relationship with Marjorie’s son, Gideon (excellent name, excellent man), and this was my first meeting with his parents.

“Oh, I doubt it,” I replied, “my work is very . . . niche.” I like to keep things quite vague, too much certainty not being a good thing in my view. People who are very certain about things aren’t usually very interesting, as Marjorie was in the process of proving.

I had been in Marjorie’s house, which I had thought was in Sheen, for about half an hour by the time of this exchange, and I felt as if I were lurching down one disastrous conversational cul-de-sac after another. The first had involved, as it happens, the location of Marjorie’s house. It wasn’t, she had assured me and in contradiction to all the available facts, in Sheen at all.

“Richmond borders,” she had said in a way that brooked no opposition. “We have a Sheen postcode because of those idiots at the Post Office, but it’s actually Richmond borders.”

“Is that an official place then, like the Scottish Borders?” I had foolishly thought she was making a joke and responded in kind.

“No.” Marjorie replied, without even the merest hint of a smile. She was, it would seem, in deadly earnest.

“Oh, I see.” I didn’t see at all. I had ended up in this position due to a clearly futile attempt to ingratiate myself with my boyfriend’s mother. Having believed myself to be in Sheen I had told Marjorie that I had once had a friend who lived there, to which she responded with an icy “and what has that got to do with me?”

I had soldiered on, not having encountered such a response before and therefore not having seen the warning signs that indicated I was digging a hole for myself. I had told Marjorie that I knew Sheen quite well on account of this friend that had lived there. I had embellished the story of my friendship somewhat (I hadn’t known the subject of my story since primary school for example, and neither had we ever gone to Zumba classes together) but I was simply trying to find some common ground, as one does in conversations. The whole exchange had left me wishing I had never heard of Sheen let alone had a passing acquaintance with someone who had once lived there. And now I was burbling on about being a writer. Would I never learn? Luckily I was saved from having to conjure up answers to any more of Marjorie’s questions by Gideon’s father.

“Drink, anyone?” asked Malcolm. He was standing in the doorway of what Gideon’s mother, I had learnt, called the lounge shaking a bottle of sweet sherry at us. He had taken Gideon off somewhere not long after our arrival leaving me alone with Marjorie, so I was inordinately pleased to see him back as it presumably meant Gideon was not far behind.

“Lovely,” I heard myself say, despite never having been especially fond of sherry, sweet or otherwise.

The house in which I found myself sitting, very uncomfortably at that moment, was a half-timbered, mock Tudor beast in a street of similarly beastly houses. It had, as Marjorie had been quick to point out, five bedrooms and three (count them!) bathrooms. She had imparted this information as we made our way from the front door to the lounge, and in such a way that one might have assumed I was an estate agent or even a prospective buyer. I half expected her to give me a brochure so keen was she to extol the virtues of her home.

I am, as a general rule, very interested in other people’s houses but this place was a very dull affair. Everything about it was done in the kind of good taste that it is difficult to dislike but which it is, at the same time, impossible to love. I was, however, trying my very hardest to love it. These people and their home were, I very much hoped, about to become my people and their home a second home to me. I was quite determined to make a good impression, but I didn’t seem to have got off to a very good start.

Meeting someone’s parents shouldn’t, by the time one is of a certain age (and I am of a certain age), matter but it does, I suppose, indicate that you are part of a ‘couple’. I must confess to being permanently confused by the rules that surround sexual pairings. At fifteen one could find oneself ‘going steady’ on the basis of a single kiss. By eighteen sleeping with someone was no guarantee that you were an item. Once into one’s twenties the idea of ‘meeting the parents’ became a useful shorthand for knowing where one stood. At this stage I was at something of a disadvantage, lacking parents whom boyfriends could meet, but until her premature death I had occasionally used my Aunt Audrey as an analogue for them. Once one passes thirty (and thirty is an ever smaller dot in my rear view mirror) the whole thing becomes, theoretically at least, somewhat less important, as people, one would hope, move beyond needing parental approval for their relationships. Even so, these people might one day be one’s own family and making a good impression is therefore to be desired.

I had approached meeting Gideon’s parents with some trepidation. I don’t have a great track record with families generally, not having had much practice, and so my trepidation had only increased when he had hinted that there might be quite a lot more riding on it than I might have wished.

“Mum’s amazing,” Gideon had told me, “we’re very close. I really trust her judgement.” This is not what anyone wants to hear when on the verge of meeting a prospective life partner’s mother. What one wants to hear is that she will love anyone that one’s prospective life partner loves or (even better) that one’s partner doesn’t care what his (or her) mother thinks. That Gideon seemed to care what his mother thought was therefore a bit of a blow and I was sent into something of a spin following Gideon’s suggestion that he and I have Sunday lunch at his parents’ home. They did, however, live quite close by, about hal

fway between the flat that I was by that time gradually moving out of, and Gideon’s home, which I was gradually moving into, so I couldn’t really come up with a reasonable excuse not to go. And it was just a Sunday lunch, a perfectly normal, casual Sunday lunch of the sort that families all over the country routinely enjoy. But however much I tried to convince myself that it was just a meal I couldn’t rid myself of an uncomfortable feeling in the pit of my stomach. What if they (and by ‘they’ I meant his mother) took a dislike to me and convinced Gideon that he should dislike me too? What if I made a fool of myself? What if I broke something? What if . . . ?

“Stop it Eve, I’m sure they’re perfectly nice people who will be delighted to meet you. They will only want Gideon to be happy, and as you make him happy it’ll be fine.” I had shared my fears with my friend Claire and she had done her best to reassure me. “Just be yourself and I’m sure they’ll warm to you,” she had said. So here I was, trying my best to impersonate someone who was just being herself, and yet waves of chilliness were coming off Gideon’s mother much as if she were a portable air conditioning unit.

“So how do you like London?” Marjorie was looking at me blankly despite having asked me a question, another in a long line of non sequiturs that had left me all at sea and rudderless, conversation-wise. She reinforced my perception that she was uninterested in my response by turning away from me as soon as she had finished speaking to stare intently at the huge diamond that adorned her ring finger.

“Oh, I love it.” I said. “Always have done. Although I have heard that there are some other excellent cities.”

“So you don’t prefer the North?” Marjorie didn’t look up as she spoke, she just kept fiddling with her ring, which was, as I’m sure she meant it to be, rather disconcerting. I carried on regardless. Why she thought I should prefer the North (I could tell from her tone that she was using a capital N), by which I presumed she meant the north of England, I had no idea, but I would be charm on a stick whatever this woman threw at me.

“Well, the countryside is very lovely,” I said, “but it’s a long way from London.” At this point Malcolm brought me a gin and tonic (I don’t know what happened to the sweet sherry, perhaps Gideon, wherever he was, had had a word). It was warm and the tonic was flat, but I wasn’t about to complain. This meeting was all about making a good impression and complaining about one’s drink didn’t come into that category.

“It must have been interesting,” I ventured, “living all over the world?” As Marjorie had expressed an interest in my thoughts on the North I thought this was a reasonable gambit, my attempts at finding common ground over Sheen having failed so spectacularly. She and Malcolm had, so Gideon told me, lived in various exotic locations courtesy of Malcolm’s career (he was now retired) as a legal something or other working for a multinational company that did something I can never quite recall.

We were by now seated in the dining room. Marjorie had demanded that we all head in there almost the very moment Malcolm had brought me my drink so I hadn’t even had a chance to take a swig of gin in the hope it might take the edge off things a bit, but at least Gideon was now back on the scene.

Once seated Marjorie had placed a pre-loaded plate of Sunday lunch in front of each of us, something that I found a little intimidating as mine contained far more than I could comfortably eat at one sitting. The only thing over which the diner had any portion control was the gravy, which sat in splendid isolation in an ornate gravy boat in the very centre of the vast table, just out of everyone’s reach.

“Not particularly,” replied Marjorie taking her seat. Before picking up her knife and fork she placed her hands, palms together and fingers lightly touching, just above her plate. For a moment I thought she was going to say grace and wondered if I should bow my head, but instead she glared into the middle distance and simply said “eat”. Neither Malcolm nor Gideon seemed to think this was odd and simply chowed down. I, somewhat gratefully, did the same as at least it meant that any attempts at conversation could, for the time being at least, be abandoned. I felt very much as rats must when they are put into mazes by people in white coats. However hard I tried I couldn’t find any subject on which Marjorie and I could have a normal discourse. Every possible conversational route led to a dead end.

“This is delicious,” I said, having shovelled down a few mouthfuls of the enormous mountain of food in front of me. It wasn’t. It looked and tasted like a pub roast meal, the kind where you can only tell what the meat is based on whether you are served apple, mint, or horseradish sauce. I assumed that the slab of grey protein on my plate was probably beef as it was accompanied by a square of barely cooked batter that I could only assume was meant to be Yorkshire pudding. There was no horseradish.

“I’d like some mustard.” Malcolm announced getting up from the table, “Anyone else want mustard?”

“You and your mustard,” hissed Marjorie, “why you have to slather good food with that muck I don’t know. I spend hours slaving in the kitchen and then you go and cover everything with mustard.” I had been about to say that I would also like some mustard but Marjorie’s antipathy towards it indicated to me that it would be politic to go without.

“Oh Mum, let him eat what he wants, he’s the one abusing his taste buds.” Gideon smiled broadly at his mother as he spoke and I saw her soften under his gaze. She clearly adored him. Upon our arrival Marjorie had hugged Gideon to her and made a grimace that implied his arrival might offer some blessed relief from the awfulness of her existence. She had refused to meet my eye. She had, rather, looked me up and down while adjusting her cardigan, a neat little affair in navy blue with gold buttons and a vaguely military epaulette on each shoulder. She had then extended her hand such a very small way that I practically fell over the threshold in an attempt to get close enough to grasp the very end of her fingers in a limp handshake. I now looked back on that experience as something of a highlight, so difficult had been everything since then.

“Yes, Ian, you’re quite right. Let him suffer!” Marjorie actually smiled as she watched Malcolm head off on his mustard mission. I had wondered if she had some sort of muscle problem that made her unable to smile as up to this point she had worn only a pinched expression that could have been annoyance, unhappiness, displeasure, or all three combined.

“Ian?” I blurted out. “Your name is Ian?”

“Mum’s always called me Ian,” Gideon explained. “She’s never liked the name Gideon. I started using it when I was about thirteen because I thought it was cooler and it sort of stuck.”

“So your name isn’t really Gideon?” I felt vaguely cheated as I liked the name Gideon. It is interesting and unusual and I was disappointed to discover that it was simply a teenage affectation. I often tell people that Eve is short for Evangeline, when in fact it says Evelyn on my birth certificate. Gideon had enthused about the name Evangeline when I had told him, so it would have been a shame if we had both been going by aliases.

“His name is Gideon. It’s a name that has been in my family for generations and which Marjorie accepted at the time of his birth.” Malcolm made this rather dramatic statement as he returned from the kitchen carrying a very small jar of sludgy brown mustard. I was even gladder I hadn’t said I wanted any.

“I did not accept it at the time,” countered Marjorie, in what was clearly a well-worn argument. “I was not given any choice. My child, my first born and I wasn’t even allowed to name him myself.” Any hint of a smile was long gone.

“Now Mum, it doesn’t really matter what I’m called does it? I’m still your first born, aren’t I?” Gideon stretched across the vast expanse of table and rubbed his mother’s arm while surreptitiously winking at me. She put her hand over his and took a deep breath as if the heavy burdens she carried (whatever these burdens might be) had been momentarily lifted by her son’s gesture.

I valiantly fought my way through the plate of food I had been allotted (although I noticed that Marjorie left most of hers

while Malcolm could clearly have eaten twice as much, he only just stopped short of actually picking up his plate and licking it) but it left me feeling even more uncomfortable than I had before lunch. I hate feeling overfull. I think that being hungry is an altogether more pleasurable experience. The difference, I think, is that hunger is easily remedied while feeling overfull can take hours to wear off. So there I was, feeling overfull, and not even as the result of a delicious meal, when Marjorie asked who wanted pudding, or sweet as she called it.

“I bought a caramel cheesecake,” she announced “from that baker on the corner, you know the one Ian.” The look Gideon gave me suggested that he didn’t. “I’ll cut it into quarters.” Oh my god, a quarter of a caramel cheesecake. I don’t have a sweet tooth so the thought of eating twenty five percent of a caramel cheesecake when I was already full to bursting made me feel physically sick.

“Oh, not for me thanks.” I said. “That was delicious but I couldn’t eat another thing.” I hoped I sounded sincere.

“I’ll pass as well Mum, but that was great.” Gideon tapped his stomach as if to prove his sincerity. We couldn’t have been more sincere.

“Your father and I can eat it tomorrow I suppose,” Marjorie huffed, “if it hasn’t gone off by then. Pass your plates.” The look on Malcolm’s face spoke clearly of his disappointment. He had not had enough main course and was now to be denied pudding. I on the other hand was even more relieved that I had refused. A cheesecake so dangerously close to going off was best avoided, even if one were hungry.

“Oh no,” I urged, “you go ahead. It’s just that I don’t often eat pudd . . . sweet. I . . .” I wasn’t sure how to continue, but felt as if I should try to rescue a situation which seemed to have made both Gideon’s parents dislike me at the same time.

“It’s no inconvenience at all,” said Marjorie in a tone that indicated that it was an inconvenience, although why someone not wanting pudding should be inconvenient I had no idea, “we’ll do whatever you want.”

In-Laws and Outlaws

In-Laws and Outlaws